Resolving a key to enterovirus infection

Researchers found a protein that's essential for an enterovirus to enter human cells. That could help the search for vaccines and treatments.

By Chris Patrick

Although not the infamous example – that title goes to poliovirus – other enteroviruses such as enterovirus D68 can cause similar paralytic symptoms in young children.

Indeed, small enterovirus D68 outbreaks have occurred in the U.S., but there’s no vaccine or specific treatment.

Now, writing in the journal Nature, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine, the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and three other institutions identified a key to enterovirus D68 infection, which could help shape future vaccinations and treatments.

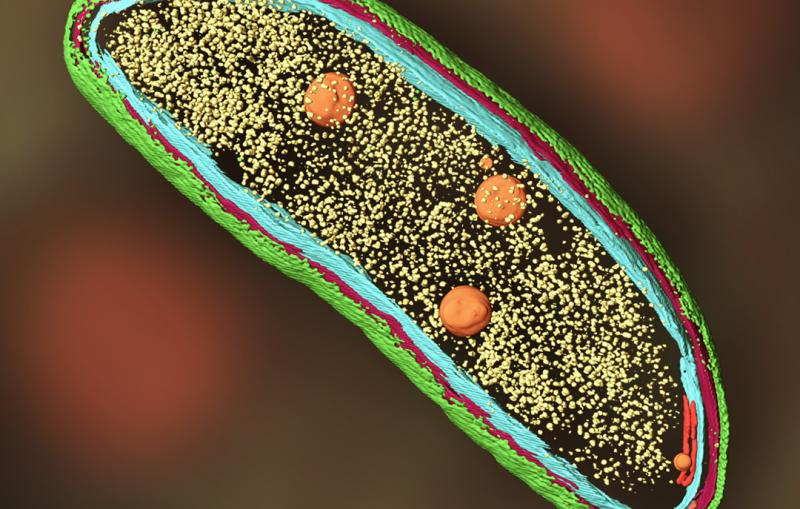

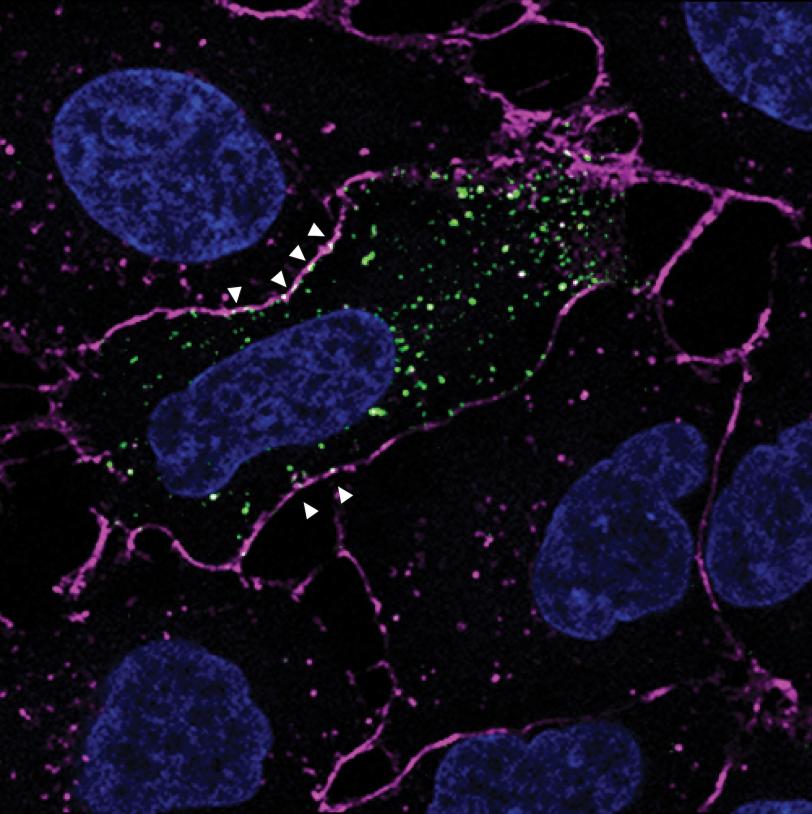

That key sits on the surface of human cells. Viruses must bind to cells’ receptor proteins to gain entry and start infection. Researchers in Stanford professor Jan Carette’s lab uncovered which receptor protein unlocks the door to the cell for enterovirus D68 by turning off the expression of each gene in the entire human genome one by one.

“It's an unbiased way of understanding which receptor is the most important for the virus out of the 20,000 proteins,” said Carette.

The result: Enterovirus D68 could not enter cells when a protein called MFSD6 was absent. What’s more, the team found that mice injected with a soluble form of the MFSD6 protein were almost completely protected from infection. The soluble form acted as a decoy receptor, coating the virus to block it from binding with actual cell receptors.

SLAC Photon Science Professor and Stanford Professor of Bioengineering and of Microbiology & ImmunologyWe demonstrated that we have imaging capabilities to retrieve structural details that can help with any emergent virus.

SLAC Experiment is First to Decipher Atomic Structure of an Intact Virus with an X-ray Laser

June 20, 2017

SLAC Experiment is First to Decipher Atomic Structure of an Intact Virus with an X-ray Laser

A ground-breaking experimental method developed by an international research team will substantially speed up protein analysis.

“Once you put the key in, no one else can put their key in the same spot,” said Lily Xu, PhD candidate at Stanford and co-first author of the results.

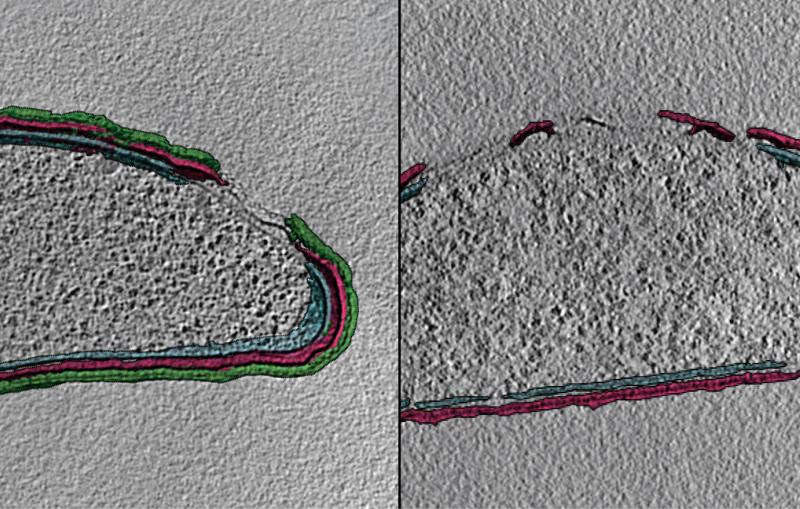

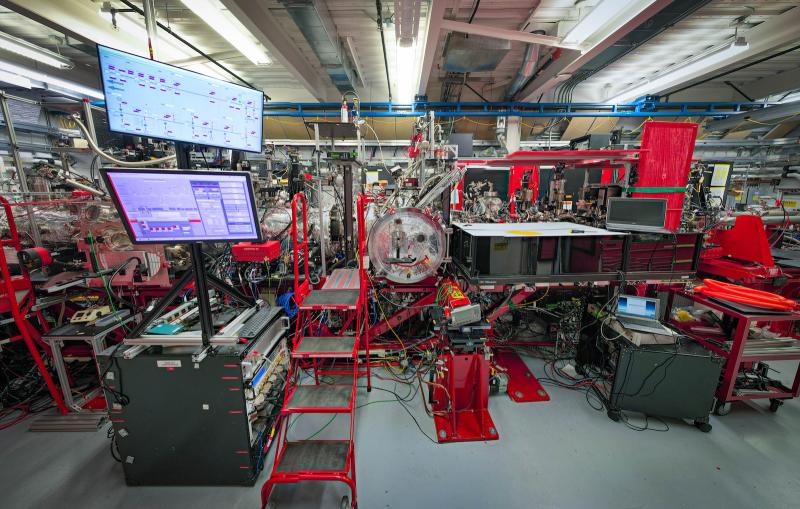

To design vaccines capable of tightly binding to the virus and blocking infection, researchers need to better understand how the virus and MFSD6 receptor protein fit together. In SLAC and Stanford professor Wah Chiu’s lab, a team used SLAC’s state-of-the-art cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) facilities to magnify the virus and protein by a factor of over 100,000. Combining this high-resolution imaging technique with the modeling skills of Stanford research scientist Grigore Pintilie, the team created a 3D model of the interaction between the virus and protein at the molecular level.

“These 3D structures are useful because they can help design other proteins or molecules that get in there to disturb the whole infection cycle,” Pintilie said.

Unexpectedly, cryo-EM revealed multiple sugars attached to the receptor protein. Stanford chemistry professor Carolyn Bertozzi and her postdoctoral fellow David Roberts used mass spectrometry to identify these sugars, which could further guide the design of vaccines.

“My dream is that our discovery can lead to the production of host-targeted therapeutics or the development of a drug or antibody that can target enterovirus D68's receptor binding site,” said Lauren Varanese, PhD candidate at Stanford and co-first author of this work.

While any potential preventatives or therapeutics based on these results wouldn’t be available for five to ten years or more, in the meantime, the structural characterization methods in this work could be extended to other viruses.

“At SLAC, we demonstrated that we have imaging capabilities to retrieve structural details that can help with any emergent virus,” said Chiu.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Stanford Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Program, the National Science Foundation, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute, the European Union’s Horizon 2024 Research and Innovation Program, and the European Union’s VIRLUMINOUS project.

Citation: Lauren Varanese et al., Nature, 25 March 2025 (10.1038/s41586-025-08908-0)

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.